Small Steps to Move Forward After Loss

The experience of losing a cherished person is profoundly difficult, and charting a course for your life in the aftermath can feel overwhelming. Moving onward doesn't mean leaving behind the memory of those you've lost. Here are some small steps to facilitate your journey of healing and help you discover a renewed sense of purpose after loss.

Photo: Siebe Warmoeskerken

GUEST POST

The following article was written by Kimberly Hayes. An author bio can be found at the end of this post.

The experience of losing a cherished person is profoundly difficult, and charting a course for your life in the aftermath can feel overwhelming. Moving onward doesn't mean leaving behind the memory of those you've lost. Here are some small steps to facilitate your journey of healing and help you discover a renewed sense of purpose after loss.

Give yourself space to mourn

Granting yourself the latitude to mourn is essential. Recognize that recovery is a lengthy journey and experiencing an array of emotions, from sorrow to frustration, is completely normal. Contrary to societal pressures to "move on," it’s crucial to give yourself time and space to grieve in a manner that is authentic to you.

Face your emotional reality

Suppressing your emotions may seem easier in the short term, but it can have long-term repercussions on your mental health. Research suggests that confronting your emotions head-on, allowing yourself to feel sadness, resentment, or bewilderment can facilitate a healthier, more holistic healing process.

Leverage your community network

During times of hardship, your friends and family can be an invaluable resource. Sharing your thoughts and emotions with them can significantly lighten your emotional load. Beyond that, your community can also provide different perspectives that might help you process your grief more thoroughly.

Craft a lasting tribute

Creating a lasting tribute for a departed loved one can offer a sense of closure and emotional relief. Options like dedicating a park bench, assembling a photo album, or hosting a memorial event can serve as enduring tokens of the joy and love that individual contributed to your life. These tangible commemorations act as perpetual reminders, helping you celebrate their life while finding peace on your own.

Create a personalized keepsake

Transforming the ashes of a departed loved one into a piece of jewelry offers a unique and tactile way to keep their memory close (EverDear is one company that offers this service). Some companies and artisans also offer the creation of blankets or stuffed animals from a loved one’s clothing. Personalized keepsakes can provide comfort and a constant reminder of the love you shared. For those interested in exploring this option, resources like everdear.co offer ideas and professional services to guide you through the process.

Bring in a furry confidant

Pets can offer emotional solace when human interaction feels too taxing. If you’re an animal lover, consider adopting a pet for emotional support. Whether it’s a dog, cat, or even a smaller animal like a guinea pig, a pet can fill your home with life and positive energy. You can find helpful pet care advice through books, websites, and pet care experts to ensure your new friend receives the best possible care. If taking on a pet full-time isn’t in the cards, many cities also offer volunteer opportunities at animal shelters.

Prioritize Holistic Wellness

Taking care of yourself may fall by the wayside during times of grief, yet it is precisely when self-care is most needed. Engage in activities that contribute to your mental, physical, and emotional well-being. Whether it’s practicing mindfulness techniques, getting regular exercise, keeping a journal, or seeking counseling, self-care should be a non-negotiable part of your healing process.

Loss is one of the harshest trials in life, but the actionable steps outlined here can help guide you through the difficult terrain of grief toward deeper purpose and a renewed sense of self. Remember, each journey of recovery is as unique as the individual walking its path. You can use these tools to embark on your own journey at your own pace, while cherishing the memory of those who have passed on.

Kimberly Hayes enjoys writing about health and wellness and created Public Health Alert to help keep the public informed about the latest developments in popular health issues and concerns.

Sources: Cognitive Psychiatry of Chapel Hill, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Matthew Funeral Home, Pets Digest, The Birds World

How to talk to someone who's grieving

It can be vulnerable and even scary to approach someone in the throes of difficult emotions, but it will mean so much to them when you do. Here are some tips for navigating this time.

Photo: @reo

If you’re the friend, family member, colleague, etc. of someone who’s grieving—welcome. You’re already taking a caring step in trying to learn more about how to understand your loved one. It can be vulnerable and even scary to approach someone in the throes of difficult emotions, but it will mean so much to them when you do. Here are some tips for navigating this time.

just try

The first step in talking to the grieving person in your life (let’s call them GPIYL from here on out) is to do it. That might seem a little obvious but it’s actually not uncommon for people to shy away from other people’s difficult emotions and just say nothing. Saying nothing is one of the worst things you can do, especially if the GPIYL is someone you’re close to. Just trying is a step that will mean so much to your loved one.

be Thoughtful, curious

If it’s the first time you’re talking to the GPIYL, a standard phrase you can say is “I’m so sorry for your loss.” You can also personalize it and say “I’m so sorry about your [insert person/pet they’ve lost].” You can also offer to them that they’re in your thoughts. Another question to ask is a simple “How are you doing?” Allow them to answer honestly, even though the answer is most likely not good.

If you’re writing it, a how-to on writing condolence notes is available here (there’s some advice overlap with this post).

Avoid hurtful phrases

There are a small handful of phrases that have come to be accepted in the grief community as more harmful than helpful, and it’s best to avoid them. Here are a few examples:

I know how you feel.

Everything happens for a reason

At least they’re not in pain.

You’re never given more than you can handle.

It was just their time.

You’ll be okay.

Also remember to be sensitive about religious beliefs. While religion may be comforting to you, if the GPIYL isn’t religious, this can be hurtful.

Tears are normal

There’s a common misconception that mentioning the loss will make the GPIYL upset because you’re “reminding them” of their loss. Two things here are true: 1) Their loss is already front-and-center in their mind, so you’re not reminding them of anything. 2) They may cry, and that’s a totally normal, healthy reaction for a grieving person to have. The best thing you can do for them in those moments is anticipate a tearful reaction and be prepared hold space for them (rather than shifting to a new topic or trying to maneuver out of your own discomfort) — consider bringing tissues. A hug may be appropriate for someone you’re close to. For colleagues, a hand on their arm or shoulder may be a better option. Consider your relationship and how the moment feels to determine the best path.

Follow their lead

The GPIYL may want to share a lot—or they may be more reserved. This is usually dependent on personality, how they’re feeling that day, and setting (for example, if they’re in the office or around a larger group, they may want to be more brief). Pay attention to whether they’re engaged—sharing more about their experience, telling stories—or whether they want to move on—changing the subject, making a joke, etc. Go where it seems they want to go.

Follow up

It’s a wonderful step to acknowledge the GPIYL’s loss early on. It’s even better to continue to acknowledge the loss over time because this is now a permanent part of their life. Recognizing anniversaries and critical milestones like birthdays, mother’s day, father’s day, etc. will go a long way. You can also just ask about the GPIYL’s lost loved one in the course of a normal day. Prompts like “Tell me a story about your dad” or “What was your son like?” can be a thoughtful way to acknowledge their loss as a huge part of their life—as well as honor the person they’ve lost.

Show, don’t tell

You may notice that the phrases “I’m here for you” or “Let me know if you need anything” aren’t in the suggested list. Those aren’t necessarily bad—they show your support—but it leaves the burden on the GPIYL to reach out. What’s * better * is to offer specific ways to help in the form of options. Some examples include:

“I can bring you dinner next week. Do you prefer lasagna or tacos?”

“I’ll watch your kids for an afternoon this weekend, which day is better—Saturday or Sunday?”

A note in closing: You might still fear that you’ll say the wrong thing. It’s okay. Do it anyway. People won’t remember what you say - they remember how you made them feel.

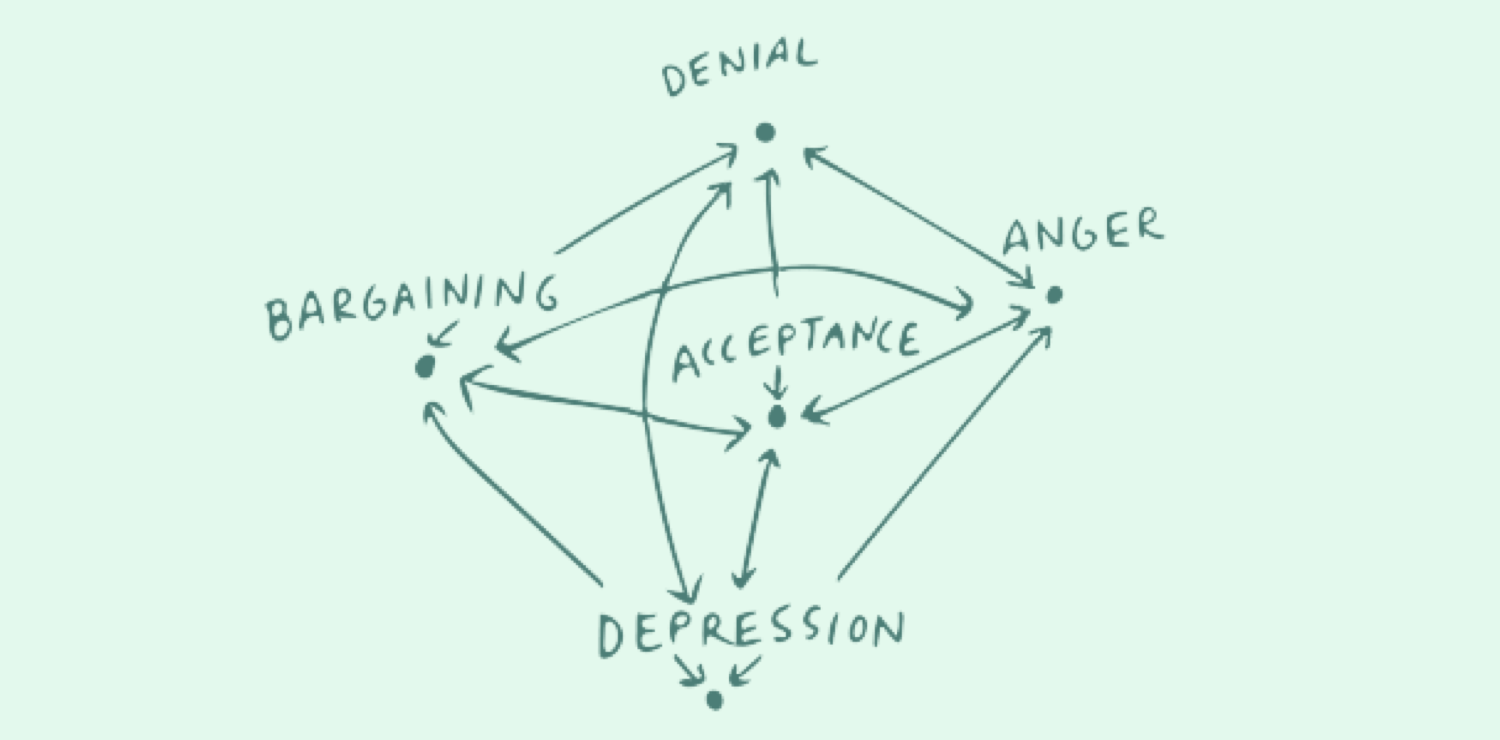

The "five stages": updating the paradigm

The idea of The Five Stages of Grief was initially created by a Swiss psychiatrist named Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who worked with people facing terminal illnesses. She introduced the model in her book On Death and Dying in 1969, and it gave words and structure to something that was ambiguous at the time. Soon this became adapted as a way of thinking about grief more generally, and it has since become a commonplace belief.

The idea of The Five Stages of Grief was initially created by a Swiss psychiatrist named Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who worked with people facing terminal illnesses. She introduced the model in her book On Death and Dying in 1969, and it gave words and structure to something that was ambiguous at the time. Soon this became adapted as a way of thinking about grief more generally, and it has since become a commonplace belief.

Here is what we’re taught that grief looks like:

It’s linear. There’s a clear start and an end. You move through each stage in order and once you reach Acceptance, the process is complete. Grief is over, you have accepted the loss, and you’re back to your old self. Never sad again.

If you’ve been through grief, you understand that this isn’t an accurate representation. In reality, it’s nonlinear and you never really stop grieving even if you accept that the loss has occurred. But this linear model is so engrained in our culture that it poses challenges to grievers and those in a griever’s orbit. It’s this flawed understanding of grief that makes people say things like:

“When you’re done grieving…”

“When she’s back to normal…”

“They just have to reach acceptance and move on.”

This perception is harmful to our understanding of the grieving process, and it requires active education to debunk it.

In reality, grief looks a little more like this:

It flows in all directions, and there’s no clear end point. The intensity of your feelings fluctuates. Even if you “reach” some semblance of Acceptance, you may still have moments of Anger or Depression. You may experience all of the stages in one day and the next day move on to one in particular. Sometimes you skip stages. Sometimes you have month-long stretches of one stage. It ebbs and flows and is anything but linear. And especially with a big loss, grief persists in some form throughout the rest of a person’s life.

I think Cheryl Strayed summed this up perfectly in one of her Dear Sugar advice columns, The Black Arc of It, on the topic of the loss of her mother and a friend’s mother, where she describes grief as a lens on her life—it’s there, during events big and small.

“[…] there isn’t one good thing that has happened to either of us that we haven’t experienced through the lens of our grief. I’m not talking about weeping and wailing every day (though sometimes we both did that). I’m talking about what goes on inside, the words unspoken, the shaky quake at the body’s core. There was no mother at our college graduations. There was no mother at our weddings. There was no mother when we sold our first books. There was no mother when our children were born. There was no mother, ever, at any turn for either one of us in our entire adult lives and there never will be.”

Grief is a cycle. It evolves and continuously unfolds, and we understand it more when we reflect back on it. That may not be how we first understood it, but that’s how it is. Once we know that, we can be kinder to people who are grieving, and we can encourage people who are grieving be kinder to themselves.

How have you experienced the “five stages” of grief? What do you think it’s missing?